Introduction

-

Attributes are implemented with a standard “template” of code

-

Remember, “attribute” is the abstract concept of some data stored in an object; “instance variable” is the way that data is actually stored

-

First, declare an instance variable for the attribute

-

Then write a “getter” method for the instance variable

-

Then write a “setter” method for the instance variable

-

With this combination of instance variable and methods, the object has an attribute that can be read (with the getter) and written (with the setter)

-

For example, this code implements a “width” attribute for the class Rectangle:

class Rectangle { private int width; public void SetWidth(int value) { width = value; } public int GetWidth() { return width; } } -

Note that there is a lot of repetitive or “obvious” code here:

- The name of the attribute is intended to be “width,” so you must

name the instance variable

width, and the methodsGetWidthandSetWidth, repeating the name three times. - The attribute is intended to be type

int, so you must ensure that the instance variable, the getter return type, and the setter parameter type are allint. Similarly, this repeats the data type three times. - You need to come up with a name for the setter’s parameter, even though it also represents the width (i.e. the new value you want to assign to the width attribute). We usually end up naming it “widthParameter” or “widthParam” or “newWidth” or “newValue.”

- The name of the attribute is intended to be “width,” so you must

name the instance variable

-

Properties are a “shorthand” way of writing this code: They implement an attribute with less repetition.

-

Note that properties are not present in every object-oriented programming language: for example, Java does not have properties.

Writing properties

-

Declare an instance variable for the attribute, like before

-

A property declaration has 3 parts:

- Header, which gives the property a name and type (very similar to variable declaration)

getaccessor, which declares the “getter” method for the propertysetaccessor, which declares the “setter” method for the property

-

Example code, implementing the “width” attribute for Rectangle (this replaces the code in the previous example):

class Rectangle { private int width; public int Width { get { return width; } set { width = value; } } } -

Header syntax:

[public/private] [type] [name] -

Convention (not rule) is to give the property the same name as the instance variable, but capitalized — C# is case sensitive

-

getaccessor: Starts with the keywordget, then a method body inside a code block (between braces)getis like a method header that always has the same name, and its other features are implied by the property’s header- Imagine that it says

public int get(): the access modifier (public) and the return type (int) are the same as in the property header - Body of

getsection is exactly the same as body of a “getter”: return the instance variable

-

setaccessor: Starts with the keywordset, then a method body inside a code block- Also a method header with a fixed name, access modifier, return type, and parameter

- Imagine that it says

public void set (int value): the access modifier (public), the return type (void), and the parameter (int value) are the same as in the property header - The return type is always

void(like a setter) - The parameter name is always “value”. In this case, that means the

parameter is

int value - Body of

setsection looks just like the body of a setter: Assign the parameter to the instance variable (and the parameter is always named “value”). In this case, that meanswidth = value

Using properties

-

Properties are members of an object, just like instance variables and methods

-

Access them with the “member access” operator, aka the dot operator

- For example,

myRect.Widthwill access the property we wrote, assumingmyRectis a Rectangle

- For example,

-

A complete example where the “length” and “width” attributes are implemented with properties:

class Rectangle { private int width; public int Width { get { return width; } set { width = value; } } private int length; public int Length { get { return length; } set { length = value; } } } -

Properties “act like” variables: you can assign to them and read from them

-

Reading from a property will automatically call the

getaccessor for that property- For example,

Console.WriteLine( $"The width is {myRectangle.Width}");will call the

getaccessor inside theWidthproperty, which in turn executesreturn widthand returns the current value of the instance variable- This is equivalent to

Console.WriteLine( $"The width is {myRectangle.GetWidth()}");using the “old” Rectangle code

-

Assigning to (writing) a property will automatically call the

setaccessor for that property, with an argument equal to the right side of the=operator- For example,

myRectangle.Width = 15;will call thesetaccessor inside theWidthproperty, withvalueequal to 15 - This is equivalent to

myRectangle.SetWidth(15);using the “old” Rectangle code

- For example,

In More Details

-

Note that in a property,

valueis what is called a contextual keyword: it is not a reserved word in C# (it could be used as an identifier), but inside a property it refers to something special, the name of the set method parameter. -

In the following code:

private int width; public int Width { get { return width; } set { width = value; } }The attribute

widthis called the Width property’s backing field: it holds the data assigned to the property. -

When the property’s get and set accessors are trivial (like the ones above), we can simply omit their bodies completely. That is, the previous

Widthproperty could be implemented usingpublic int Width { get; set; }This is called automatic properties (or auto-properties). Note that in this case, we do not need to declare the property’s backing field (that is, no need to have

private int width;), but cannot refer to it! -

Conversely, the get and set accessors can contain arbitrarily convoluted code:

public int Length { get { return length; } set { if (value < 0) { length = -value; } else if (value == 0) { length = 1; } else { length = value; } } } -

Note however that if either the set or get accessor is not the “trivial” one, then automatic properties cannot be used and the other accessor must be specified.

- For example, in the above code, simply writing

get;instead ofget { return length; }would give a compilation error.

- For example, in the above code, simply writing

-

Note that properties can exist without backing field, and they can be read-only (that is, without a set accessor) or write-only (that is, without a get accessor, but this is more rare).

-

An example of read-only property is as follows:

class Circle { public decimal Diameter { get; set; } // The constructor below sets the value // of the property's backing field through // the property's set accessor. public Circle(decimal dP) { Diameter = dP; } // The Radius property below is // 1. read-only (no set accessor), // 2. without a backing field. public decimal Radius { get { return Diameter / 2; } } }

-

-

It is possible to set a “custom default value” for properties using a property initializer, as follows:

public double Diameter { get; set; } = -1;In this case, the property’s backing field value will be -1 by default. Properties with an initializer can be read-only:

public int MaximumValue { get; } = 999; -

Finally, properties can be

staticas well:public static string Explanation { get; set; } = "A Circle has for radius its diameter divided by 2.";This means that the property is shared among all instances of the class. It also means that the property can be accessed without creating an object (instantiating the class) first. For example, you might access the above property this way:

Console.WriteLine(Circle.Explanation);and its value can be changed, for instance by appending a

stringto it:Circle.Explanation += "\nIts circumference is π multiplied by its diameter.";

Putting together some of the elements discussed above, we can get for example the following:

class Circle

{

public decimal Diameter { get; set; }

// The constructor below sets the value

// of the property's backing field through

// the property's set accessor.

public Circle(decimal dP)

{

Diameter = dP;

}

// The Radius property below is

// 1. read-only (no set accessor),

// 2. without a backing field.

public decimal Radius

{

get { return Diameter / 2; }

}

// The Circumference property below

// is also read-only, and without

// a backing field.

public decimal Circumference

{

get { return Diameter * PI; }

}

// Using properties with a *static* attribute:

private static string explanation =

"The diameter is the radius times 2, the circumference is the diameter times pi.";

public static string Explanation

{

get { return explanation; }

set { explanation = value; }

}

// Using static, read-only property:

public static decimal PI { get; } = 3.1415926535897931M;

// Pretty much the same as

// public const decimal PI = 3.1415926535897931M;

public override string ToString()

{

return "Your circle has a diameter of "

+ Diameter

+ "\nA radius of "

+ Radius

+ "\nCircumference of "

+ Circumference;

}

}Properties in UML Class Diagrams

Simple Notation

-

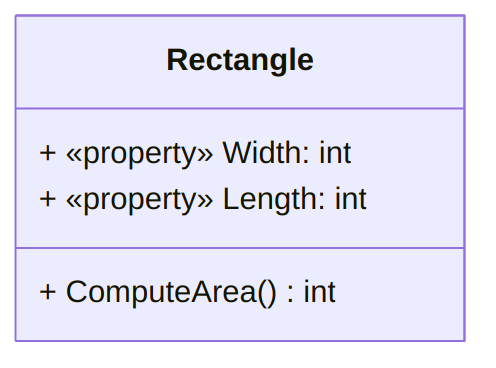

Since properties represent (or, rather, allow to access) attributes, they go in the “attributes” box (the second box).

-

If a property will simply “get” and “set” an instance variable of the same name, you do not need to write the instance variable in the box, especially if those instance variables are not used anywhere other than through the property

- No need to write both the property

Widthand the instance variablewidth

- No need to write both the property

-

Syntax:

[+/-] «property» [name]: [type](where “<<property>{=html}>” is sometimes used in place of «property»). -

Note that the access modifier (+ or -) is for the property, not the instance variable, so it is + if the property is

public(which it usually is). -

Example for

Rectangle, assuming we converted both attributes to use properties instead of getters and setters:

-

We no longer need to write all those setter and getter methods, since they are “built in” to the properties

More Accurate Notation

In general, instead of writing for example

+ «properties» Explanation: stringone can write

+ «get, set» Explanation: stringor even

+ «set» Explanation: string

+ «get» Explanation: stringThe benefit of this notation is that read-only properties can easily be

integrated in the UML class diagram, by simply omitting the «set»

line:

+ «get» Radius : decimalProperties and Security

The following discussion is related to the general topic of

try-catch-finally

scope but

can be read independently.

Properties are extremely useful to insure that an attribute will never receive a “forbidden” value (for example, outside a range). Since every access to the attribute is “safeguarded” by the property, it can provide some security only if used correctly.

For example, consider the following code:

using System;

class PropertySafety

{

private string sensibleData;

public string SensibleData

{

set

{

sensibleData = value;

if (value == "Forbidden word")

{

Console.WriteLine("Intrusion detected, aborting!");

throw new AccessViolationException();

}

}

get { return sensibleData; }

}

}It may be easy to consider that sensibleData will never receive the

value "Forbidden word" if every access to sensibleData is made

through the property SensibleData. However, this is plain wrong!

Indeed, consider the following (where you may replace the exception bit

with return; if you are not familiar with this concept yet).

using System;

class Program

{

static void Main()

{

PropertySafety test = new PropertySafety();

try

{

test.SensibleData = "Forbidden word";

}

catch (AccessViolationException ex)

{

Console.WriteLine(ex.Message);

}

Console.WriteLine(test.SensibleData);

}

}It will display

Intrusion detected, aborting!

Attempted to read or write protected memory. This is often an indication that other memory is corrupt.

Forbidden wordWhere the last line indicate that the attribute was set to

"Forbidden word"!

The correct fix is to first test, then set, so that an incorrect

value would never be assigned. In the previous example, simply

moving sensibleData = value; to the end of the set would fix this

issue.