Motivation

- One of the benefit of Object-Oriented Programming is to re-use the same class to handle multiple instantiations. This saves the programmer having to repeat or copy the same code again and again.

- But classes can themselves re-use code from other classes: this similarly saves the programmer from having to copy the same code again and again.

- Consider for example that a programmer has to write a class for cars,

a class for bikes, and a class for planes.

- All classes will share some attributes: they will all need, for example, an attribute for their number of wheels, one for their passenger capacity, one for their average speed, one for their average price per mile, and so on.

- All classes may also share some method: typically, how the number of wheels can be accessed, or how to convert their price per mile to a price per kilometer.

- However, some attributes will be proper to some classes: fork length makes sense only for bikes1, maximum altitude only makes sense for planes, trunk size only make sense for cars, etc.

- This is an example of inheritance: the programmer will implement one class for vehicle containing all the shared attributes and methods, and will have the class for e.g., bikes, inherits from the vehicle class.

- The most general class is called the base class (or superclass). The most particular class is called the derived class (or subclass).

Vehicle Example

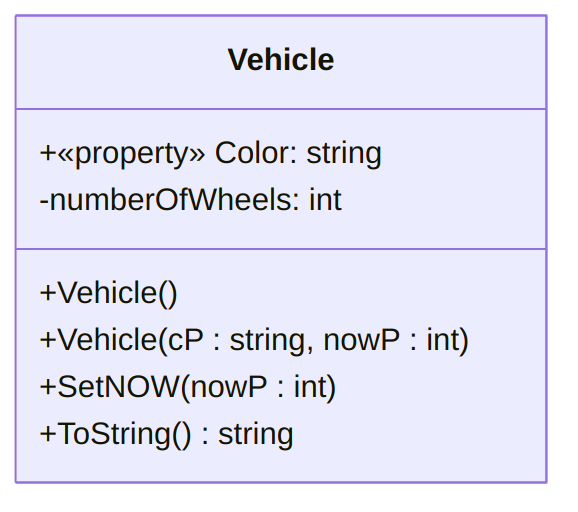

Consider the following class:

with the following implementation:

using System;

public class Vehicle

{

public string Color { get; set; }

private int numberOfWheels;

public void SetNOW(int nowP)

{

if (nowP > 0)

numberOfWheels = nowP;

else

numberOfWheels = -1;

// We could also decide to throw an exception here, using e.g.

// throw new ArgumentException();

}

public Vehicle()

{

Color = "undefined";

numberOfWheels = -1;

}

public Vehicle(string cP, int nowP)

{

Color = cP;

numberOfWheels = nowP;

// We could also use our SetNOW method, as follows:

// SetNOW(nowP);

}

public override string ToString()

{

return $"Number of wheels: {numberOfWheels}"

+ $"\nColor: {Color}";

}

}and say that we want to extend it to accommodate bikes. Bikes have, in

addition to a color and a number of wheels, a fork length. Note that no

other vehicle have a fork length, so it does not make sense to add this

attribute to the Vehicle class.

A possible implementation is as follows:

public class Bike : Vehicle

{

public double ForkLength { get; set; }

public Bike()

{

ForkLength = -1;

SetNOW(2);

// or

// base.SetNOW(2);

}

public Bike(string cP, double flP)

: base(cP, 2)

{

ForkLength = flP;

}

public override string ToString()

{

return base.ToString() + $"\nFork Length: {ForkLength}";

}

}Note:

-

The

: Vehicleon the first line, that makeBikea derived class fromVehicle. AnyBikeobject will have all the attributes and properties of theVehicleclass, in addition to its methods. For example, we can have:Bike test2 = new Bike(); test2.Color = "Green";and the

VehicleColoraccessor will be used, sinceBikedoes not have an accessor forColor. -

Implicitly, the

Bike()constructor starts by calling theVehicle()constructor, so thatColorandnumberOfWheelsare actually set to"undefined"and-1, respectively. -

That

SetNOWinto theBike()constructor actually refers to theSetNOWmethod in theVehicleclass. A way of being more explicit would have been to writebase.SetNOWinstead ofSetNOW. In either case, the value-1is overriden by2(since every bike has 2 wheels). -

The

: base(cP, 2)instructs to call theVehicle(string cP, int nowP)constructor, passing it the values

cPand2(once again since every bike has 2 wheels). -

The

overridekeyword “discards” theVehicleToStringmethod to replace it with a customToStringmethod for theBikeclass. Note that we can still access what theVehiclemethod returns usingbase.ToString(). Note that, in this particular, we have no choice but to call this baseToStringmethod, since we have no way of accessingnumberOfWheelsfrom theBikeclass: this attribute is private to theVehicleclass, and has no getter.

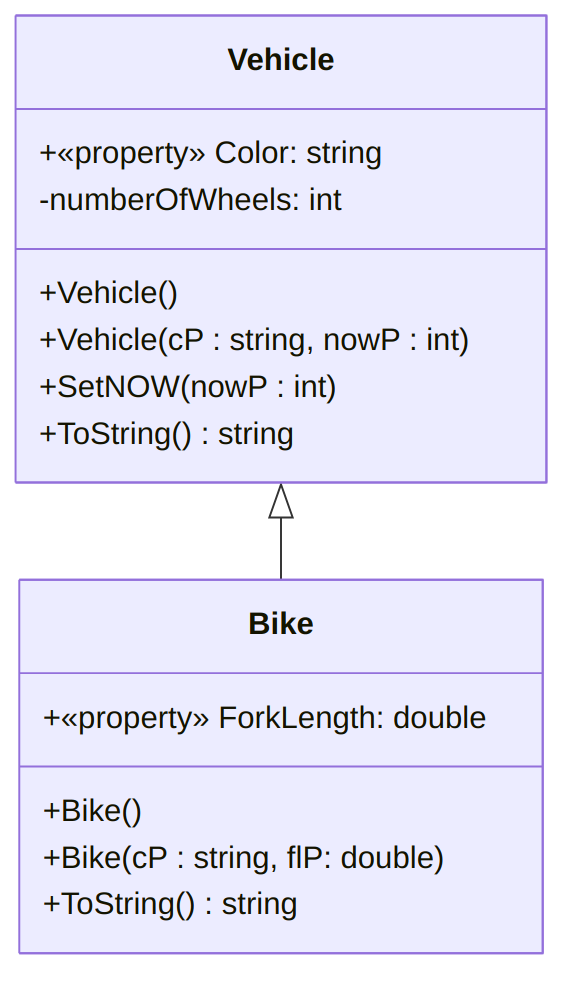

The inheritance is represent in UML as follows:

Observe that the ToString is indicated in the Bike class: this is an

indication that the Vehicle’s ToString method is actually overriden

in the Bike derived class.

Note that inheritance can be “chained”, as Bike could itself be the

base class for a Bicycle class that could have e.g. a saddleType

attribute (noting that a motorbike does not have a saddle, but a seat).

We could then obtain a code as follows:

public class Bicycle : Bike

{

private string saddleType;

public Bicycle()

{

saddleType = "undefined";

}

public Bicycle(string cP, double flP, string sdtP)

: base(cP, flP)

{

saddleType = sdtP;

}

public override string ToString()

{

return base.ToString() + $"\nSaddle Type: {saddleType}";

}

}Footnotes

-

We use “bike” to refer to both bicycles and motorcycles. ↩