Class and Object Basics

- Classes vs. Objects

- A class is a specification, blueprint, or template for an object; it is the code that describes what data the object stores and what it can do

- An object is a single instance of a class, created using its “template.” It is executing code, with specific values stored in each variable

- To instantiate an object is to create a new object from a class

- Object design basics

- Objects have attributes: data stored in the object. This data is different in each instance, although the type of data is defined in the class.

- Objects have methods: functions that use or modify the object’s data. The code for these functions is defined in the class, but it is executed on (and modifies) a specific object

- Encapsulation: An important principle in class/object design

- Attribute data is stored in instance variables, a special kind of variable

- Called “instance” because each instance, i.e. object, has its own copy of them

- Encapsulation means instance variables (attributes) are “hidden”

inside an object: other code cannot access them directly

- Only the object’s own methods can access the instance variables

- Other code must “ask permission” from the object in order to read or write the variables

Writing Our First Class

- Designing the class

- Our first class will be used to represent rectangles; each instance (object) will represent one rectangle

- Attributes of a rectangle:

- Length

- Width

- Methods that will use the rectangle’s attributes

- Get length

- Get width

- Set length

- Set width

- Compute the rectangle’s area

- Note that the first four are a specific type of method called “getters” and “setters” because they allow other code to read (get) or write (set) the rectangle’s instance variables while respecting encapsulation

The Rectangle class:

class Rectangle

{

private int length;

private int width;

public void SetLength(int lengthParameter)

{

length = lengthParameter;

}

public int GetLength()

{

return length;

}

public void SetWidth(int widthParameter)

{

width = widthParameter;

}

public int GetWidth()

{

return width;

}

public int ComputeArea()

{

return length * width;

}

}Let’s look at each part of this code in order.

- Attributes

- Each attribute (length and width) is stored in an instance variable

- Instance variables are declared similarly to “regular” variables, but with one additional feature: the access modifier

- Syntax:

[access modifier] [type] [variable name] - The access modifier can have several values, the most common of

which are

publicandprivate. (There are other access modifiers, such asprotectedandinternal, but in this class we will only be usingpublicandprivate). - An access modifier of

privateis what enforces encapsulation: when you use this access modifier, it means the instance variable cannot be accessed by any code outside theRectangleclass - The C# compiler will give you an error if you write code that

attempts to use a

privateinstance variable anywhere other than a method of that variable’s class

- SetLength method, an example of a “setter” method

- This method will allow code outside the

Rectangleclass to modify aRectangleobject’s “length” attribute - Note that the header of this method has an access modifier, just like the instance variable

- In this case the access modifier is

publicbecause we want to allow other code to call theSetLengthmethod - Syntax of a method declaration:

[access modifier] [return type] [method name]([parameters]) - This method has one parameter, named

lengthParameter, whose type isint. This means the method must be called with one argument that isinttype.- Similar to how

Console.WriteLinemust be called with one argument that isstringtype — theConsole.WriteLinedeclaration has one parameter that isstringtype. - Note that it is declared just like a variable, with a type and a name

- Similar to how

- A parameter works like a variable: it has a type and a value, and you can use it in expressions and assignment

- When you call a method with a particular argument, like 15, the parameter is assigned this value, so within the method’s code you can assume the parameter value is “the argument to this method”

- The body of the

SetLengthmethod has one statement, which assigns the instance variablelengthto the value contained in the parameterlengthParameter. In other words, whatever argumentSetLengthis called with will get assigned tolength - This is why it is called a “setter”:

SetLength(15)will setlengthto 15.

- This method will allow code outside the

- GetLength method, an example of a “getter” method

- This method will allow code outside the

Rectangleclass to read the current value of aRectangleobject’s “length” attribute - The return type of this method is

int, which means that the value it returns to the calling code is anintvalue - Recall that

Console.ReadLine()returns astringvalue to the caller, which is why you can writestring userInput = Console.ReadLine(). TheGetLengthmethod will do the same thing, only with anintinstead of astring - This method has no parameters, so you do not provide any arguments when calling it. “Getter” methods never have parameters, since their purpose is to “get” (read) a value, not change anything

- The body of

GetLengthhas one statement, which uses a new keyword:return. This keyword declares what will be returned by the method, i.e. what particular value will be given to the caller to use in an expression. - In a “getter” method, the value we return is the instance variable

that corresponds to the attribute named in the method.

GetLengthreturns thelengthinstance variable.

- This method will allow code outside the

- SetWidth method

- This is another “setter” method, so it looks very similar to

SetLength - It takes one parameter (

widthParameter) and assigns it to thewidthinstance variable - Note that the return type of both setters is

void. The return typevoidmeans “this method does not return a value.”Console.WriteLineis an example of avoidmethod we’ve used already. - Since the return type is

void, there is noreturnstatement in this method

- This is another “setter” method, so it looks very similar to

- GetWidth method

- This is the “getter” method for the width attribute

- It looks very similar to

GetLength, except the instance variable in thereturnstatement iswidthrather thanlength

- The ComputeArea method

- This is not a getter or setter: its goal is not to read or write a single instance variable

- The goal of this method is to compute and return the rectangle’s area

- Since the area of the rectangle will be an

int(it is the product of twoints), we declare the return type of the method to beint - This method has no parameters, because it does not need any arguments. Its only “input” is the instance variables, and it will always do the same thing every time you call it.

- The body of the method has a

returnstatement with an expression, rather than a single variable - When you write

return [expression], the expression will be evaluated first, then the resulting value will be used by thereturncommand - In this case, the expression

length * widthwill be evaluated, which computes the area of the rectangle. Since bothlengthandwidthareints, theintversion of the*operator executes, and it produces anintresult. This resultingintis what the method returns.

Using Our Class

- We’ve written a class, but it does not do anything yet

- The class is a blueprint for an object, not an object

- To make it “do something” (i.e. execute some methods), we need to instantiate an object using this class

- The code that does this should be in a separate file (e.g. Program.cs), not in Rectangle.cs

- Here is a program that uses our

Rectangleclass:

using System;

class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

Rectangle myRectangle = new Rectangle();

myRectangle.SetLength(12);

myRectangle.SetWidth(3);

int area = myRectangle.ComputeArea();

Console.WriteLine(

"Your rectangle's length is "

+ $"{myRectangle.GetLength()}, and its width is "

+ $"{myRectangle.GetWidth()}, so its area is {area}."

);

}

}- Instantiating an object

- The first line of code creates a

Rectangleobject - The left side of the

=sign is a variable declaration — it declares a variable of typeRectangle- Classes we write become new data types in C#

- The right side of the

=sign assigns this variable a value: aRectangleobject - We instantiate an object by writing the keyword

newfollowed by the name of the class (syntax:new [class name]()). The empty parentheses are required, but we will explain why later. - This statement is really an initialization statement: It declares and assigns a variable in one line

- The value of the

myRectanglevariable is theRectangleobject that was created bynew Rectangle()

- The first line of code creates a

- Calling setters on the object

- The next two lines of code call the

SetLengthandSetWidthmethods on the object - Syntax:

[object name].[method name]([argument]). Note the “dot operator” between the variable name and the method name. SetLengthis called with an argument of 12, solengthParametergets the value 12, and the rectangle’slengthinstance variable is then assigned this value- Similarly,

SetWidthis called with an argument of 3, so the rectangle’swidthinstance variable is assigned the value 3

- The next two lines of code call the

- Calling ComputeArea

- The next line calls the

ComputeAreamethod and assigns its result to a new variable namedarea - The syntax is the same as the other method calls

- Since this method has a return value, we need to do something with the return value — we assign it to a variable

- Similar to how you must do something with the result (return value)

of

Console.ReadLine(), i.e.string userInput = Console.ReadLine()

- The next line calls the

- Calling getters on the object

- The last line of code displays some information about the rectangle object using string interpolation

- One part of the string interpolation is the

areavariable, which we’ve seen before - The other interpolated values are

myRectangle.GetLength()andmyRectangle.GetWidth() - Looking at the first one: this will call the

GetLengthmethod, which has a return value that is anint. Instead of storing the return value in anintvariable, we put it in the string interpolation brackets, which means it will be converted to a string usingToString. This means the rectangle’s length will be inserted into the string and displayed on the screen

Flow of Control with Objects

-

Consider what happens when you have multiple objects in the same program, like this:

class Program { static void Main(string[] args) { Rectangle rect1; rect1 = new Rectangle(); rect1.SetLength(12); rect1.SetWidth(3); Rectangle rect2 = new Rectangle(); rect2.SetLength(7); rect2.SetWidth(15); } }- First, we declare a variable of type

Rectangle - Then we assign

rect1a value, a newRectangleobject that we instantiate - We call the

SetLengthandSetWidthmethods usingrect1, and theRectangleobject thatrect1refers to gets itslengthandwidthinstance variables set to 12 and 3 - Then we create another

Rectangleobject and assign it to the variablerect2. This object has its own copy of thelengthandwidthinstance variables, not 12 and 3 - We call the

SetLengthandSetWidthmethods again, usingrect2on the left side of the dot instead ofrect1. This means theRectangleobject thatrect2refers to gets its instance variables set to 7 and 15, while the otherRectangleremains unmodified

- First, we declare a variable of type

-

The same method code can modify different objects at different times

- Calling a method transfers control from the current line of code (i.e. in Program.cs) to the method code within the class (Rectangle.cs)

- The method code is always the same, but the specific object that gets modified can be different each time

- The variable on the left side of the dot operator determines which object gets modified

- In

rect1.SetLength(12),rect1is the calling object, soSetLengthwill modifyrect1SetLengthbegins executing withlengthParameterequal to 12- The instance variable

lengthinlength = lengthParameterrefers torect1’s length

- In

rect2.SetLength(7),rect2is the calling object, soSetLengthwill modifyrect2SetLengthbegins executing withlengthParameterequal to 7- The instance variable

lengthinlength = lengthParameterrefers torect2’s length

Accessing object members

-

The “dot operator” that we use to call methods is technically the member access operator

-

A member of an object is either a method or an instance variable

-

When we write

objectName.methodName(), e.g.rect1.SetLength(12), we are using the dot operator to access the “SetLength” member ofrect1, which is a method; this means we want to call (execute) theSetLengthmethod ofrect1 -

We can also use the dot operator to access instance variables, although we usually do not do that because of encapsulation

-

If we wrote the

Rectangleclass like this:class Rectangle { public int length; public int width; }Then we could write a

Mainmethod that uses the dot operator to access thelengthandwidthinstance variables, like this:static void Main(string[] args) { Rectangle rect1 = new Rectangle(); rect1.length = 12; rect1.width = 3; }But this code violates encapsulation, so we will not do this.

Method calls in more detail

-

Now that we know about the member access operator, we can explain how method calls work a little better

-

When we write

rect1.SetLength(12), theSetLengthmethod is executed withrect1as the calling object — we are accessing theSetLengthmember ofrect1in particular (even though every Rectangle has the sameSetLengthmethod) -

This means that when the code in

SetLengthuses an instance variable, i.e.length, it will automatically accessrect1’s copy of the instance variable -

You can imagine that the

SetLengthmethod “changes” to this when you callrect1.SetLength():public void SetLength(int lengthParameter) { rect1.length = lengthParameter; }Note that we use the “dot” (member access) operator on

rect1to access itslengthinstance variable. -

Similarly, you can imagine that the

SetLengthmethod “changes” to this when you callrect2.SetLength():public void SetLength(int lengthParameter) { rect2.length = lengthParameter; } -

The calling object is automatically “inserted” before any instance variables in a method

-

The keyword

thisis an explicit reference to “the calling object”-

Instead of imagining that the calling object’s name is inserted before each instance variable, you could write the

SetLengthmethod like this:public void SetLength(int lengthParameter) { this.length = lengthParameter; } -

This is valid code (unlike our imaginary examples) and will work exactly the same as our previous way of writing

SetLength -

When

SetLengthis called withrect1.SetLength(12),thisbecomes equal torect1, just likelengthParameterbecomes equal to 12 -

When

SetLengthis called withrect2.SetLength(7),thisbecomes equal torect2andlengthParameterbecomes equal to 7

-

Methods and instance variables

-

Using a variable in an expression means reading its value

-

A variable only changes when it is on the left side of an assignment statement; this is writing to the variable

-

A method that uses instance variables in an expression, but does not assign to them, will not modify the object

-

For example, consider the

ComputeAreamethod:public int ComputeArea() { return length * width; }It reads the current values of

lengthandwidthto compute their product, but the product is returned to the method’s caller. The instance variables are not changed. -

After executing the following code:

Rectangle rect1 = new Rectangle(); rect1.SetLength(12); rect1.SetWidth(3); int area = rect1.ComputeArea();rect1has alengthof 12 and awidthof 3. The call torect1.ComputeArea()computes , and theareavariable is assigned this return value, but it does not changerect1.

Methods and return values

-

Recall the basic structure of a program: receive input, compute something, produce output

-

A method has the same structure: it receives input from its parameters, computes by executing the statements in its body, then produces output by returning a value

-

For example, consider this method defined in the Rectangle class:

public int LengthProduct(int factor) { return length * factor; }Its input is the parameter

factor, which is anint. In the method body, it computes the product of the rectangle’s length andfactor. The method’s output is the resulting product.

-

-

The

returnstatement specifies the output of the method: a variable, expression, etc. that produces some value -

A method call can be used in other code as if it were a value. The “value” of a method call is the method’s return value.

-

In previous examples, we wrote

int area = rect1.ComputeArea();, which assigns a variable (area) a value (the return value ofComputeArea()) -

The

LengthProductmethod can be used like this:Rectangle rect1 = new Rectangle(); rect1.SetLength(12); int result = rect1.LengthProduct(2) + 1;When executing the third line of code, the computer first executes the

LengthProductmethod with argument (input) 2, which computes the product . Then it uses the return value ofLengthProduct, which is 24, to evaluate the expressionrect1.LengthProduct(2) + 1, producing a result of 25. Finally, it assigns the value 25 to the variableresult.

-

-

When writing a method that returns a value, the value in the

returnstatement must be the same type as the method’s return type-

If the value returned by

LengthProductis not anint, we will get a compile error -

This will not work:

public int LengthProduct(double factor) { return length * factor; }Now that

factorhas typedouble, the expressionlength * factorwill need to implicitly convertlengthfrominttodoublein order to make the types match. Then the product will also be adouble, so the return value does not match the return type (int). -

We could fix it by either changing the return type of the method to

double, or adding a cast tointto the product so that the return value is still anint

-

-

Not all methods return a value, but all methods must have a return type

-

The return type

voidmeans “nothing is returned” -

If your method does not return a value, its return type must be

void. If the return type is notvoid, the method must return a value. -

This will cause a compile error because the method has a return type of

intbut no return statement:public int SetLength(int lengthP) { length = lengthP; } -

This will cause a compile error because the method has a return type of

void, but it attempts to return something anyway:public void GetLength() { return length; }

-

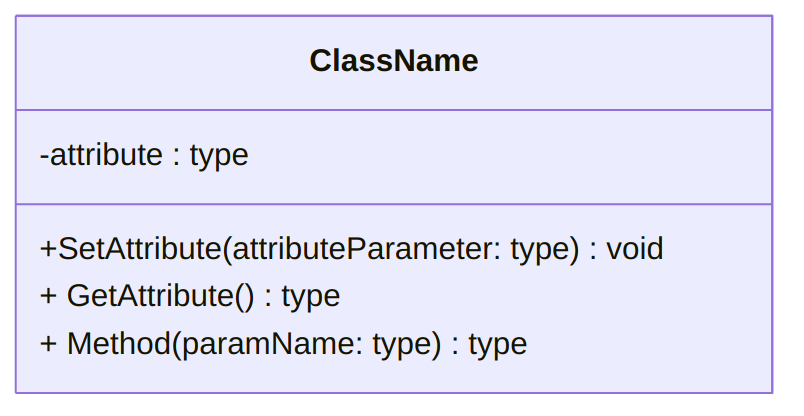

Introduction to UML

-

UML is a specification language for software

- UML: Unified Modeling Language

- Describes design and structure of a program with graphics

- Does not include “implementation details,” such as code statements

- Can be used for any programming language, not just C#

- Used in planning/design phase of software creation, before you start writing code

- Process: Determine program requirements Make UML diagrams Write code based on UML Test and debug program

-

UML Class Diagram elements

- Top box: Class name, centered

- Middle box: Attributes (i.e. instance variables)

- On each line, one attribute, with its name and type

- Syntax:

[+/-] [name]: [type] - Note this is the opposite order from C# variable declaration: type comes after name

- Minus sign at beginning of line indicates “private member”

- Bottom box: Operations (i.e. methods)

- On each line, one method header, including name, parameters, and return type

- Syntax:

[+/-] [name]([parameter name]: [parameter type]): [return type] - Also backwards compared to C# order: parameter types come after parameter names, and return type comes after method name instead of before it

- Plus sign at beginning of line indicates “public”, which is what we want for methods

-

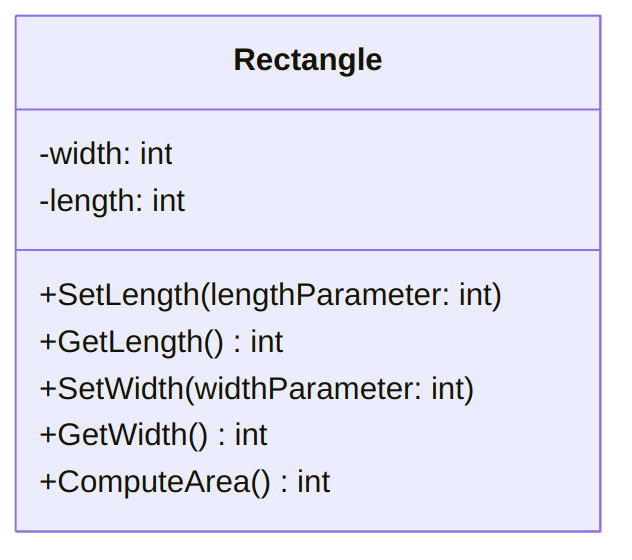

UML Diagram for the Rectangle class

- Note that when the return type of a method is

void, we can omit it in UML - In general, attributes will be private (

-sign) and methods will be public (+sign), so you can expect most of your classes to follow this pattern (-s in the upper box,+s in the lower box) - Note that there is no code or “implementation” described here: it

does not say that

ComputeAreawill multiplylengthbywidth

- Note that when the return type of a method is

-

Writing code based on a UML diagram

- Each diagram is one class, everything within the box is between the class’s header and its closing brace

- For each attribute in the attributes section, write an instance

variable of the right name and type

- See ”- width: int”, write

private int width; - Remember to reverse the order of name and type

- See ”- width: int”, write

- For each method in the methods section, write a method header with

the matching return type, name, and parameters

- Parameter declarations are like the instance variables: in UML they have a name followed by a type, in C# you write the type name first

- Now the method bodies need to be filled in - UML just defined the interface, now you need to write the implementation

Variable Scope

Instance and local variables

-

Instance variables: Stored (in memory) with the object, shared by all methods of the object. Changes made within a method persist after method finishes executing.

-

Local variables: Visible to only one method, not shared. Disappear after method finishes executing. Variables we’ve created before in the

Mainmethod (they are local to theMainmethod!). -

Example: In class Rectangle, we have these two methods:

public void SwapDimensions() { int temp = length; length = width; width = temp; } public int GetLength() { return length; }tempis a local variable withinSwapDimensions, whilelengthandwidthare instance variables- The

GetLengthmethod cannot usetemp; it is visible only toSwapDimensions - When

SwapDimensionschangeslength, that change is persistent — it will still be different whenGetLengthexecutes, and the next call toGetLengthafterSwapDimensionswill return the new length - When

SwapDimensionsassigns a value totemp, it only has that value within the current call toSwapDimensions— afterSwapDimensionsfinishes,tempdisappears, and the next call toSwapDimensionscreates a newtemp

Definition of scope

-

Variables exist only in limited time and space within the program

-

Outside those limits, the variable cannot be accessed — e.g. local variables cannot be accessed outside their method

-

Scope of a variable: The region of the program where it is accessible/visible

- A variable is “in scope” when it is accessible

- A variable is “out of scope” when it does not exist or cannot be accessed

-

Time limits to scope: Scope begins after the variable has been declared

- This is why you cannot use a variable before declaring it

-

Space limits to scope: Scope is within the same code block where the variable is declared

- Code blocks are defined by curly braces: everything between matching

{and}is in the same code block - Instance variables are declared in the class’s code block (they are

inside

class Rectangle’s body, but not inside anything else), so their scope extends to the entire class - Code blocks nest: A method’s code block is inside the class’s code block, so instance variables are also in scope within each method’s code block

- Local variables are declared inside a method’s code block, so their scope is limited to that single method

- Code blocks are defined by curly braces: everything between matching

-

The scope of a parameter (which is a variable) is the method’s code block - it is the same as a local variable for that method

-

Scope example:

public void SwapDimensions() { int temp = length; length = width; width = temp; } public void SetWidth(int widthParam) { int temp = width; width = widthParam; }- The two variables named

temphave different scopes: One has a scope limited to theSwapDimensionsmethod’s body, while the other has a scope limited to theSetWidthmethod’s body - This is why they can have the same name: variable names must be unique within the variable’s scope. You can have two variables with the same name if they are in different scopes.

- The scope of instance variables

lengthandwidthis the body of classRectangle, so they are in scope for both of these methods

- The two variables named

Variables with overlapping scopes

-

This code is legal (compiles) but does not do what you want:

class Rectangle { private int length; private int width; public void UpdateWidth(int newWidth) { int width = 5; width = newWidth; } } -

The instance variable

widthand the local variablewidthhave different scopes, so they can have the same name -

But the instance variable’s scope (the class

Rectangle) overlaps with the local variable’s scope (the methodUpdateWidth) -

If two variables have the same name and overlapping scopes, the variable with the closer or smaller scope shadows the variable with the farther or wider scope: the name will refer only to the variable with the smaller scope

-

In this case, that means

widthinsideUpdateWidthrefers only to the local variable namedwidth, whose scope is smaller because it is limited to theUpdateWidthmethod. The linewidth = newWidthactually changes the local variable, not the instance variable namedwidth. -

Since instance variables have a large scope (the whole class), they will always get shadowed by variables declared within methods

-

You can prevent shadowing by using the keyword

this, like this:class Rectangle { private int length; private int width; public void UpdateWidth(int newWidth) { int width = 5; this.width = newWidth; } }Since

thismeans “the calling object”,this.widthmeans “access thewidthmember of the calling object.” This can only mean the instance variablewidth, not the local variable with the same name -

Incidentally, you can also use

thisto give your parameters the same name as the instance variables they are modifying:class Rectangle { private int length; private int width; public void SetWidth(int width) { this.width = width; } }Without

this, the body of theSetWidthmethod would bewidth = width;, which does not do anything (it would assign the parameterwidthto itself).

Constants

-

Classes can also contain constants

-

Syntax:

[public/private] const [type] [name] = [value]; -

This is a named value that never changes during program execution

-

Safe to make it

publicbecause it cannot change — no risk of violating encapsulation -

Can only be built-in types (

int,double, etc.), not objects -

Can make your program more readable by giving names to “magic numbers” that have some significance

-

Convention: constants have names in ALL CAPS

-

Example:

class Calendar { public const int MONTHS = 12; private int currentMonth; //... }The value “12” has a special meaning here, i.e. the number of months in a year, so we use a constant to name it.

-

Constants are accessed using the name of the class, not the name of an object — they are the same for every object of that class. For example:

Calendar myCal = new Calendar(); decimal yearlyPrice = 2000.0m; decimal monthlyPrice = yearlyPrice / Calendar.MONTHS;

Reference Types: More Details

- Data types in C# are either value types or reference types

- This difference was introduced in an earlier lecture (Datatypes and Variables)

- For a value type variable (

int,long,float,double,decimal,char,bool) the named memory location stores the exact data value held by the variable - For a reference type variable, such as

string, the named memory location stores a reference to the value, not the value itself - All objects you create from your own classes, like

Rectangle, are reference types

- Object variables are references

-

When you have a variable for a reference type, or “reference variable,” you need to be careful with the assignment operation

-

Consider this code:

using System; class Program { static void Main(string[] args) { Rectangle rect1 = new Rectangle(); rect1.SetLength(8); rect1.SetWidth(10); Rectangle rect2 = rect1; rect2.SetLength(4); Console.WriteLine( $"Rectangle 1: {rect1.GetLength()} " + $"by {rect1.GetWidth()}" ); Console.WriteLine( $"Rectangle 2: {rect2.GetLength()} " + $"by {rect2.GetWidth()}" ); } } -

The output is:

Rectangle 1: 4 by 10 Rectangle 2: 4 by 10 -

The variables

rect1andrect2actually refer to the sameRectangleobject, sorect2.SetLength(4)seems to change the length of “both” rectangles -

The assignment operator copies the contents of the variable, but a reference variable contains a reference to an object — so that’s what gets copied (in

Rectangle rect2 = rect1), not the object itself -

In more detail:

Rectangle rect1 = new Rectangle()creates a new Rectangle object somewhere in memory, then creates a reference variable namedrect1somewhere else in memory. The variable namedrect1is initialized with the memory address of the Rectangle object, i.e. a reference to the objectrect1.SetLength(8)reads the address of the Rectangle object from therect1variable, finds the object in memory, and executes theSetLengthmethod on that object (changing its length to 8)rect1.SetWidth(10)does the same thing, finds the same object, and sets its width to 10Rectangle rect2 = rect1creates a reference variable namedrect2in memory, but does not create a new Rectangle object. Instead, it initializesrect2with the same memory address that is stored inrect1, referring to the same Rectangle objectrect2.SetLength(4)reads the address of a Rectangle object from therect2variable, finds that object in memory, and sets its length to 4 — but this is the exact same Rectangle object thatrect1refers to

-

- Reference types can also appear in method parameters

-

When you call a method, you provide an argument (a value) for each parameter in the method’s declaration

-

Since the parameter is really a variable, the computer will then assign the argument to the parameter, just like variable assignment

- For example, when you write

rect1.SetLength(8), there is an implicit assignmentlengthParameter = 8that gets executed before executing the body of theSetLengthmethod

- For example, when you write

-

This means if the parameter is a reference type (like an object), the parameter will get a copy of the reference, not a copy of the object

-

When you use the parameter to modify the object, you will modify the same object that the caller provided as an argument

-

This means objects can change other objects!

-

For example, imagine we added this method to the Rectangle class:

public void CopyToOther(Rectangle otherRect) { otherRect.SetLength(length); otherRect.SetWidth(width); }It uses the

SetLengthandSetWidthmethods to modify its parameter,otherRect. Specifically, it sets the parameter’s length and width to its own length and width. -

The

Mainmethod of a program could do something like this:Rectangle rect1 = new Rectangle(); Rectangle rect2 = new Rectangle(); rect1.SetLength(8); rect1.SetWidth(10); rect1.CopyToOther(rect2); Console.WriteLine($"Rectangle 2: {rect2.GetLength()} " + $"by {rect2.GetWidth()}");- First it creates two different

Rectangleobjects (note the two calls tonew), then it sets the length and width of one object, usingrect1.SetLengthandrect1.SetWidth - Then it calls the

CopyToOthermethod with an argument ofrect2. This transfers control to the method and (implicitly) makes the assignmentotherRect = rect2 - Since

otherRectandrect2are now reference variables referring to the same object, the calls tootherRect.SetLengthandotherRect.SetWidthwithin the method will modify that object - After the call to

CopyToOther, the object referred to byrect2has a length of 8 and a width of 10, even though we never calledrect2.SetLengthorrect2.SetWidth

- First it creates two different

-